In this blog article, the team at RJG Technologies outline how to develop a robust design for successful manufacturing.

There are a lot of moving parts when it comes to injection moulding part and mould design. Between product design, material selection, mould design, and processing, collaboration is key to ensure a successful project. There are hundreds of areas that need to be covered on each of those projects, but RJG is going to focus on the stages of product design and launch.

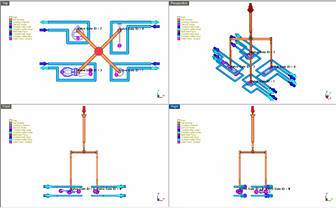

Keep reading as RJG walks through the steps it took to create what would have been its giveaway for NPE 2021: golf tools (image 1).

Design for Manufacturing Concerns

There are many areas that we need to look at when evaluating a part for the draft: radius, datum, dimensions, tolerances, quoted cycle times, and potential non-conformities for moulding or assembly. We looked at all of those areas for this project, but there were three main concerns we watched out for.

1. Wall Thickness: In the golf part, wall thickness varies from 0.020 in. (0.508 mm) to 0.750 in. (19.05 mm) depending on the area (shown above in image 2). This presents issues with fill/pack/cool, yielding high risk for differing shrink rates, warp, sinks, and voids. That meant we needed to modify the parts to allow for a mould with no actions. This was done by changing the geometry and adding draft.

2. Assembly: Another concern we had was being able to fit the ball marker into the divot fork upon assembly. Ideally, they would be one piece instead of rattling around loose in the golfer’s pocket.

3. Accuracy: The last area of concern was the straightness of the tee. Let’s be honest, when I hook a ball, I blame the club, the ball, the weather, or maybe even the tee… anything but my terrible swing. So we needed to get the tee perfectly straight to remove that as a possibility for blame.

In-Mould Rheology

In-mould rheology can be used to improve the simulation material characterisation files. This allows for the most accurate simulations to help ensure we understand what’s going to occur in the moulding process and how to head off any issues before we cut steel.

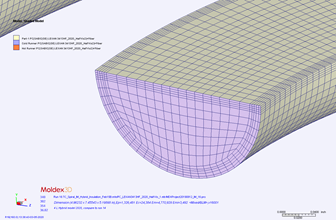

The focus of in-mould rheology is to understand the accuracy of the values in the simulation material file for viscosity and thermal properties. Shown below in image 3 is a polycarbonate material from within the simulation software showing the two viscosity parameters we will be evaluating.

These values impact the slope of the cavity pressure curve in simulation as well as the arrival time of the melt front to a sensor node in the simulation.

To complete this testing, we have a spiral mould with a constant thickness equipped with cavity pressure and temperature sensors (shown below in image 4).

There are several instances when we want to look at utilising in-mould rheology:

-

For relatively new materials

-

If a material file in simulation has not been updated for an extended period of time

-

To understand how different additives impact processing (which impacts part performance)

When setting simulation for in-mould rheology, we used 15 layers within the mesh model to improve accuracy (shown below in image 5). The sensor nodes within the mesh model replicate the placement of sensors in the actual mould, so we have the best data set possible.

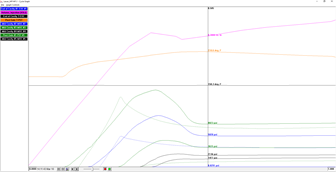

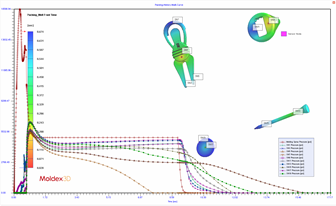

We then ran a baseline simulation with the unaltered material file to determine what shifts need to be made and by how much. In image 6 below, the dotted line is the template that we generate in simulation and then download into the eDART so we could compare. The solid line of the same colour represents the actual sensors data. For now, we will just focus on the viscosity properties, and we can see that the arrival time and slope of the curves during filling are a touch off.

After this initial run, we made adjustments to the viscosity parameters to improve the arrival time and slope of the simulation to best fit reality. We see below in image 7 that the arrival time is nearly identical after these adjustments, and the slope during filling is much closer. We followed a similar protocol to evaluate thermal conductivity during the cooling phase.

Material Selection

When considering material selection for the golf part, there were several things to think about. The part will be a one-time or limited use, so there were no true functional requirements to consider. We also wanted a minimal carbon footprint with the best parts and lowest possible scrap.

We carefully analysed our resin options:

-

Fossil Fuel Base: less expensive, easier to acquire and colour

-

Biodegradable: expensive and difficult to colour but earth-friendly

-

ABS: middle of the road material, flows well, releases easily from the mould

-

PC: shows visually what’s happening internally with the void formation and stress

-

PLA: the same resin the bottom of the K-cup is made out of

After working with our marketing department, we decided to test the following materials:

-

Fossil Fuel Based

-

PP – Exxon AX03

-

ABS – Toyolac® 100

-

-

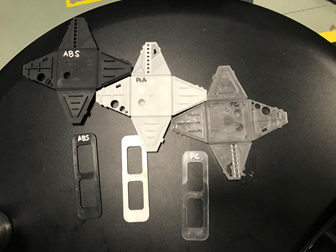

Biodegradable (image 8)

-

ABS – Trilac® ABS-RC3000

-

Polycarbonate – Trieco 3A00 I(R)

-

PLA (Polylactic Acid) – Terratek® BD5175

-

All things considered, we decided to move forward with the biodegradable ABS, which we will be running in multiple colours at NPE 2021. We will be working through the in-mould rheology exercise again to evaluate the impacts of the pre-coloured material.

Mould Design and Moulding Machine

Now we must begin to define the box we are working within. Several points need to be taken into consideration early on to eliminate the risk of degradation of additives, such as colour, release agents, fibres, or even the base polymer chain, including:

-

Gate placement: should be in the thickest section (if feasible and does not create a safety hazard)

-

Size of the gate: should be based on the wall thickness and shear rate

-

Shear heating of the resin

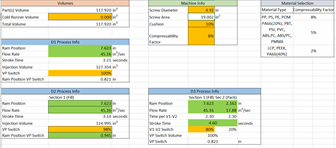

Water will be placed to achieve a uniform part and mould temperature across all four parts, shown in image 9 below.

The mould will need to last decades and likely need to run many materials over the course of its existence. Some materials require low polish, while others require a high polish level. To be the most accommodating possible, we selected an H13 and coated it with a Nickle Boron to help reduce friction.

Machine limitations of shot size, flow rates, injection pressure, clamp tonnage, tie bar spacing, and mould height were also considered.

Support pillars will be placed under the high-pressure points within the cavity to minimise mould deflection and increase mould life. Cavity pressure sensors will be placed at the end of the fill to detect short shots and post gate to control the Decoupled III process and cavity temperature sensors will be placed to activate valve gates based on the material flow front.

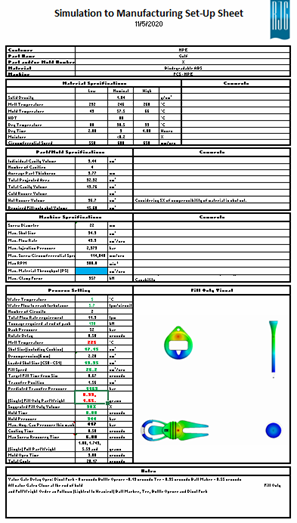

Processing

Before running a simulation based on material, tolerance, and other criteria, we need to determine the best process strategy. Image 10 below is an initial set-up sheet. We calculated shot size and flow rates based on machine capability and material limitations. This helps to ensure that the number of simulation iterations is kept to a minimum, allowing for faster turn-around due to planning. We also calculated proper gate size based on wall thickness where the gate will be placed and maximum shear rate of the material and in conjunction with the machine flow rate capability.

Due to the volume, thickness, and flow length differences, we chose to fill the parts sequentially (filling the thickest/largest volume first, while filling the smallest/thinnest last). The objective is for all four cavities to hit the end of the fill at the same time (or as close as possible). In the simulation, we are activating valve gates based on sensor nodes. These sensor nodes will correlate with actual cavity temperature sensors that will detect the flow front of material and be activated through the eDART. By activating valve gates based on the flow front arrival, the process can handle much larger viscosity changes (especially when running multiple colours in the same mould).

The moving boundary shown in image 11 represents the movement of the screw during injection and helps to improve predicted accuracy of injection and cavity pressures. This is a standard Decoupled II process—we can see the screw moving but no material in the cavity yet. This is due to material compressibility (which varies in semi-crystalline and amorphous resin). This compression before movement increases required injection pressure and can impact accuracy if not modelled correctly. This sequence isn’t exactly what we want, but with another iteration, we can get all cavities to hit the end of fill at almost the same time.

After that is complete, we can then simulate the mould deflection based on actual pressures in the cavity using the moulding simulation. The analysis below in image 12 shows that there is minimal support and mould deflection of 0.0018 in. (0.048mm).

Outputs

We know that doing simulation work can head off issues, so it’s valuable if you’re running moulds with or without sensors. If sensor technology is not used, we can output from simulation a set-up sheet for the machine(s) that the mould will run in, shown below in image 13. With process development completed and a known process window, the time and cost spent getting the mould up running can be significantly reduced. Of course, small adjustments will still likely need to be made.

For moulders who do utilise cavity or temperature sensor technology, there is another layer that gets even closer to better results. Not only would you get the process sheet we discussed previously, but we take the sensor curves generated in simulation and download them into the eDART® or CoPilot®. This now gives you a cavity template to follow rather than just machine variables. We all know that processing from the plastic’s point of view from in the mould cavity has the highest repeatability over time.

Conclusion

No matter the industry, material, machine, or process strategy, using tools like TZERO and sensors will help get you running consistent quality much faster (and we all know time is money).